This is another excerpt from my novel in progress, Skin of Glass.

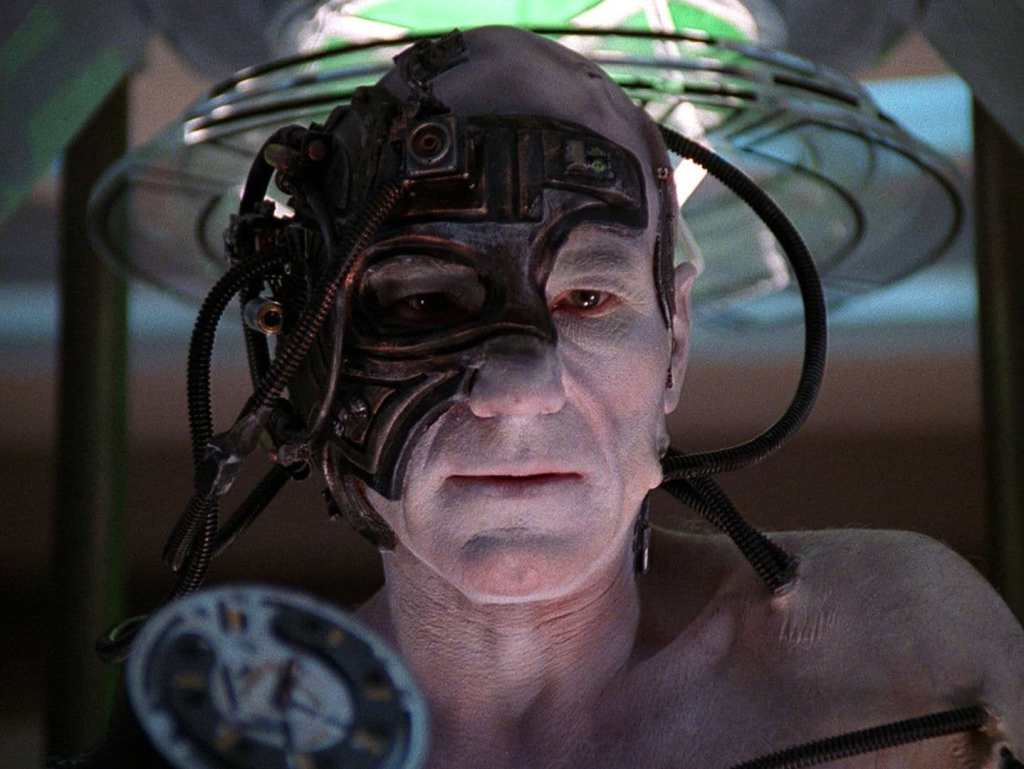

Five-Happiness-Restaurant-San-Francisco (Photo credit: foodnut.com)

November 1990. At the end of his shift at the bookstore, Ethan intends to grab a sandwich from the deli and go home to work on his paper on symbolism and surrealism in Modern Greek Literature. But once he’s behind the wheel of his car, he’s thinking not about Greek Literature but about Eve. Again. His plan falls apart at the first red light; fifteen minutes later he’s in a phone booth on Van Ness Avenue dialing her number. It’s rush hour and the blare of traffic and stink of exhaust fumes make him dizzy. His nerves are frayed and his reflexes dulled from lack of sleep. If he doesn’t finish his paper by the end of the week, he’s going to nail an incomplete. It goes without saying he isn’t getting any writing done.

When he started daydreaming about Eve, it was a harmless fantasy. Then he began seeing her face everywhere. It’s reached the point where he has to talk to her, at least hear her voice, hear her say his name, if only to tell him to go to hell. He feels as though he’s waiting for the results of some medical tests that mean everything: life or death.

She answers the phone distractedly, but after he identifies himself, she says, “Ethan!” clearly surprised to hear from him. Possibly pleased? Or is he projecting? When he says nothing else, she asks him if anything’s wrong.

“No, nothing’s wrong. I just wondered…have you eaten yet? Do you want to get something to eat?” There’s no warmth in his voice, no invitation. His hand is clamped around the receiver, and he’s staring through the grimy glass enclosure at the three lanes of cars stopped at the corner for the light.

“With you, you mean?”

The light turns green. The booming bass from a passing car vibrates along the pavement and travels up Ethan’s body, all the way to the hand holding the receiver. He says, “Yes,” amid the sudden crescendo of gunned engines. He feels his mouth form the word, but he can’t hear his own voice. When she doesn’t respond immediately, he wonders if he actually said it out loud, if she heard him. He won’t say it again.

“Sure,” she says. “But I need to change; I just got home. Can I meet you somewhere?”

He hadn’t thought that far, but the image of her sitting across from him at that Chinese restaurant pops into his head. He doesn’t remember the name, but she does, and they agree to meet there in an hour. When he hangs up, he looks through the phone book for the address, then walks swiftly toward his car, which is parked illegally across the street. The darkness seems to have deepened in the space of his telephone call, or in response to it. He could go to the library and get a little research done. At least he’d be doing something productive. But until he sees her and settles this thing somehow, it’s hopeless to try to carry on with his everyday life.

The restaurant is on Grant Avenue in Chinatown, an area he doesn’t know. He drives across town and spends twenty minutes trying to find parking. Even this time of year, the street is noisy and crowded, bustling with automobile and foot traffic. He parks on a side street a few blocks from the restaurant and tries to walk off some of his nervous energy. It’s cold and windy; he moves with his head down, his hands stuffed into the pockets of a gray down vest, not looking at anyone, and not bothering to glance into any of the lighted store windows filled with cheap souvenirs and garish clothing. What exactly is he doing? It would have been better for everyone, including him, if Eve hadn’t been home, or if she’d refused to meet him. In fact, he thinks she should have refused. He’s already mentally convicting them of betraying Jesse, although the only betrayal so far is his, and it doesn’t have to go any further.

He enters the restaurant, immediately fortified a little by the aroma of garlic and ginger. The petite smiling hostess shows him to a table for two, assuring him she’ll watch for Eve. He orders a beer, shrugs out of the down vest, and leans back in his chair. He looks around, trying to remember where they sat when they were here for the birthday party. Several tables had been placed end-to-end. But it was a long time ago, and all he can picture is Eve and the heavy red draperies and table linen.

He glimpses himself in the mirrored panel of a room divider and almost doesn’t recognize himself. He looks like a vagrant, somewhat sinister. He goes to the restroom to splash his face with water, run his fingers through his unruly mass of hair, and wash his hands. The whites of his eyes are so bloodshot they look pink; there are dark circles under them. A clear, firm voice in his head says, Leave now. Just go. But he can’t.

He’s back in his seat taking a sip of beer when the hostess leads Eve to the table, both of them smiling as though they share a happy secret. Ethan rises but doesn’t touch her, doesn’t smile, just says her name, “Eve.” Once they’re seated, a waiter places a pot of tea on the table and hands them menus. Eve slips her arms out of her camel’s hair coat and lets it fall against the back of her chair. What now?

She takes in the room. “I haven’t been here since January.” The memory seems a pleasant one. “Have you?”

“Me?” He shakes his head. “I almost never eat out. That was a special occasion.” He has one hand around the cold, wet glass of beer. He can barely look at her. All he registers is that she’s wearing a pale yellow sweater with a high neckline, and her hair is shorter than he remembers. They focus on their menus, although he isn’t really reading his. “You’re more experienced with this. Why don’t you choose?”

“But what do you like?”

“Anything. I’m not fussy.” Afraid he’s being rude, he adds, “I’m sure whatever you select will be perfect.”

Her skin is almost white. Porcelain. He feels vulgar and coarse by comparison. Classic beauty and the beast; they shouldn’t even be occupying the same table. She studies the menu pages, humming to herself so softly and unselfconsciously it melts him, the same way Molly melts him when she sits on the floor singing made-up songs to her dolls.

Eve recites her choices aloud, then repeats them to their waiter, adding, “not too hot, please.” The waiter—Chinese, with close-cropped hair and wire-rimmed glasses—bows and nods.

“Jesse always gets the Kung Pao Tofu here. This is his favorite restaurant in the City.”

Ethan sighs. Why hadn’t that occurred to him? This is such an amazingly bad idea. Jesse is going to be here at the table all evening. Well, it’s what he deserves.

“Did I say something wrong?”

He shakes his head, suddenly drained, too tired to be here, to be doing this. “No, no. This is probably a bad idea. I’m pretty tired. Not very good company. I’m sorry.”

“You just need some food.” She pours tea for both of them. “Are you taking any classes this semester?”

He laughs. “One. Modern Greek Literature. Which I’m doing my absolute best to fail.”

They pass the time talking about teachers, classes, and homework. When their food arrives, he picks up his fork, but Eve insists he learn how to use the chopsticks. It takes him a few minutes to grasp the concept, and even then he’s far from adept. They slip from his fingers, clattering against the plate, and he drops bits of food on their way to his mouth. The rice is especially tricky. They both laugh at his attempts, but she encourages him and his technique improves.

He asks her when she started doing art and learns her father’s an architect.

“I used to go to his office with him, and sometimes I’d draw these fantastic, elaborate houses while he was working. I wanted to do what he did. In fact I would have gone into architecture, but I couldn’t hack all the math. It would have been a much better career choice than fine art, that’s for sure. But I’m rethinking that.”

“Rethinking what?”

“What I want to be when I grow up. It’s one thing to make art for yourself, but I’m not sure about trying to earn a living with it. And I can’t really say I’m driven by any grande artistic vision. I was planning to be an illustrator, now that I’ve finally mastered the human form.”

“What do you mean?”

“Learning how to draw people was hard. I was always pretty good at drawing things—structures, nature. Inanimate objects, I guess you could say.”

“It’s funny how that works. I still have trouble writing descriptions. If I don’t pay attention my stories all end up taking place in fields of white space. I guess I’m not very visual. I mean I see things but—”

“The trick is learning how to feel with your eyes.”

“Feel with your eyes?”

“I read about it in a book my father gave me.”

“An art book?”

“No. A novel. My Name is Asher Lev.”

“Oh. Chaim Potok. I read that one. Long time ago. So you know how to do that? Feel things with your eyes?”

She blushes. “Sort of. When I first tried it I focused very, very intently, but the harder I tried the more frustrating it was. I couldn’t get it. In high school I discovered the secret. Pot.”

They burst into laughter.

“Is your father an artist, too?”

“Technically, no, but he could be. He used to do these exquisite architectural renderings. When you’d see one you’d just want to live in it. In that world, I mean. But he doesn’t have time for it anymore. I’m not as good as he is.” She shrugs. “But this semester I have a photography course and I love it. Maybe because it’s new. But I can imagine being a photographer a lot easier than I can imagine being an artist. And I mean to get off the dole as soon as I can.”

“The dole?”

“Being supported by my father. He does some work for free, for community groups and nonprofit organizations, and I feel like such a leech that he’s still supporting me. I’d like to be on the other end, you know? Be making some kind of a contribution the way he does. Besides, I’m sure he has better things to do with his hard-earned money.”

“Well, speaking as a Dad,” Ethan says, with mock gravity, “I can’t imagine there’s anything I’d rather do with my money than spend it on my daughter. If I had any money, that is.”

“You say that now, when Molly’s, what? Three? Wait till you’re closing in on twenty years of financial support.”

“So would you stop doing art if you became a photographer?”

“No. I like to play with colors, textures, get the feeling of something or someone down on paper, to preserve it. Everything’s so temporary. This way I can preserve the memories.”

“Hm. Like impressionist photographs.”

“Hey, I hadn’t thought of that!”

By the time they’re finishing the lukewarm tea, he feels as though he’s been on a brief vacation. “This was delicious, every bit of it—at least every bit I managed to get into my mouth.”

“All you need is practice. But you did great for the first time.”

Her lipstick is gone, her blue eyes shining; she looks happy and relaxed, hunched over her teacup tucking strands of red hair behind her left ear. He feels a wave of affection for her. Affection. Nothing more. And he won’t ask for more; he won’t betray Jesse.

The waiter brings the check on a small black plastic tray. There’s a single fortune cookie on it. Ethan barely notices the waiter slip a cookie into each of Eve’s hands, he does it so quickly and smoothly. She blushes again, very becoming, and her eyes widen. She glances at Ethan and then at the departing waiter.

Ethan grins at her embarrassment. “There must be some super special fortunes in those cookies.” He reaches for the one on the tray, opens it with a single snap, pulls out the narrow piece of paper, and reads it aloud. “The road to knowledge begins with the turn of a page.” He rolls his eyes and crunches the pieces of cookie in his mouth. “Preaching to the converted here.”

She opens first one cookie, then the other, reading her fortunes to herself. Ethan waits for her to read them aloud, but she gives him a crooked half-smile and pockets them. He teases her about it, but she won’t tell him what they say. He pulls his wallet out and lays some bills on the tray. She slips her arms into her coat and he shrugs into his vest. On the way out, they nod to the waiter, who bows again and thanks them.

“Where’s your car? I’ll walk you to it.”

“It’s only a block away,” she says. “You don’t have to do that.”

“But I want to.” He presses the palm of his hand against her back, steering her in the direction she indicated. They walk slowly, in a comfortable silence. When they get to her car, she rummages through her handbag for her keys, and a small brush falls to the pavement.

“I’ve got it.” Ethan retrieves the brush and hands it to her. She reaches for it carefully, not touching his outstretched palm.

Suddenly she looks away. “Do you ever feel like you’re living someone else’s life? Like no matter how good you are you’ll never measure up?”

There’s a lump in his throat; all he can do is nod.

“Oh, listen to me,” she says, her tone shifting. “As if I have anything to complain about.”

But of course he knows what she means. He knows exactly what she means.

“Thank you, Ethan. That was wonderful. Such a nice surprise on a cold, gloomy day.”

He wants to say something light in response, but they’re standing too close, and instead of saying anything, he grasps her shoulders, pulls her toward him, and kisses her hard on the lips—waiting for her to push him away, maybe even hit him. But she sways unsteadily toward him so he folds his arms around her and she relaxes against him. A sigh escapes from one or both of them, and they stay like that, standing on the dark street in the cold, next to her car.

- eve dreams (givemeadaisy.com)