not completely exploded: Saul Bellow via Counting Crows

When I think back, it seems the reading came first. It had to have come first. But no; that’s not right. Listening came first: listening to other people reading to me…listening to all the stories. Then came learning to read.

In the beginning, I really did read about Dick and Jane and Sally and Spot. Later I read the Black Stallion books by Walter Farley. I can’t recall a time when I didn’t have a library card, so I always had books to read. Eventually I noticed some books in the bookcase in the living room. One was A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith. It wasn’t until after I devoured the book that I learned it was banned by the Catholic Church, in which I happened to be being raised. Don’t know why my parents had it. But knowing the book was banned wouldn’t have stopped me from reading it.

By then I was probably writing, too. I dabbled in short stories and poetry, but what I primarily wrote were plays. Yes, plays were the thing for me during adolescence and into high school. In the sixth grade, I wrote, cast, and directed three plays. In high school, I moved on to writing a “novel” in longhand in four shorthand notebooks that were passed around among my classmates.

At 16, I got a job in a library where I had time and opportunity to come in contact with plenty of books I probably wouldn’t have otherwise. The Spark of Life by Erich Maria Remarque, author of All Quiet on the Western Front (which I have not read) was so arresting I couldn’t get the images out of my head. I searched for a copy of it for years (just like I searched for a copy of No Sun in Venice by the Modern Jazz Quartet). Finally found one at a used bookstore in Sonoma! I still have it.

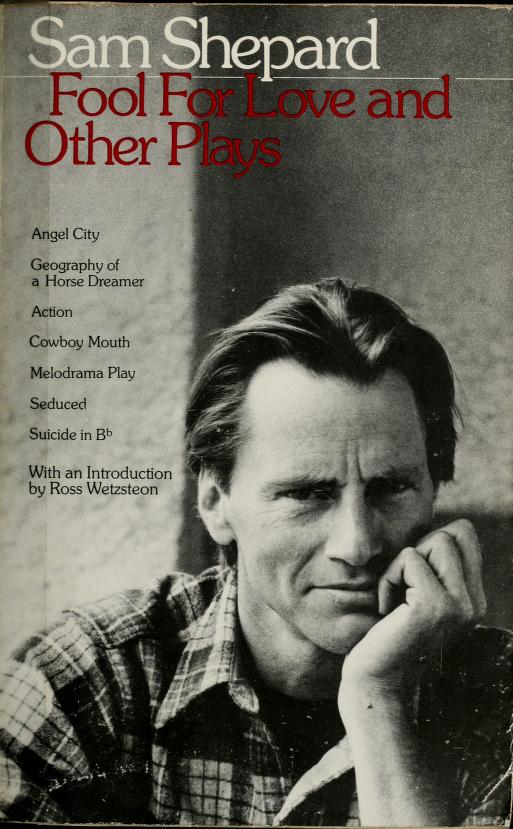

Can’t remember when I stopped writing plays, but I continued to read them from high school through the 80s. No Exit (Sartre). Waiting for Godot (Beckett). Sam Shepard wrote a lot of plays, and I read a lot of them. It worked out. Is publishing plays for people to read as common now as it was back then? I don’t look for them, so I don’t know.

I had a fairly long poetry phase that lasted beyond playwriting, but I haven’t written poetry in some time. Poetry as a form seems less alien to me than plays. But I think you have to (or you do, anyway) enter a particular unhurried state of mind and perception in order to write poetry, if not to read it. Some days that’s appealing to me, abstractly.

In college, I read so much good fiction. Saul Bellow, John Updike, Kurt Vonnegut, John Irving, J.D. Salinger, Joyce Carol Oates…these were some of the authors I kept going back to. As did my friends. We talked about what we were reading (and talked and talked and talked). My story about that period of time is that yes, we were young and somewhat ridiculous, but we were also passionately interested in ideas. We cared about what it meant to live a life. We tried to home in on what’s important, on what really matters. It felt like that was what we were supposed to do in college. Is that true? Or was it our age…or the age?

Aside from the high school attempt, I have had two novels in progress since the 90s. One is essentially complete; the other about two-thirds. I haven’t actively worked on either one in nearly 10 years. I don’t exclusively read books about the brain and behavior, but I almost exclusively read non-fiction now. This is the longest period of time since I’ve been able to read and write fiction that I haven’t been doing it. I’ve been noticing these pieces missing from my life for a while and more recently lamenting the loss. A yearning to get them back—or get back to them—has been steadily infiltrating my stream of consciousness.

The other day, The Rain King, a song by Counting Crows, came around in the rotation on my iPod, and although I’ve been listening to this song since it was released in the 90s and always knew what it was alluding to, the mention of Henderson got my attention this time. Henderson the Rain King is one of the books I read back in the day when one of my friends and I were on a Saul Bellow kick. This line from Herzog (1964) is among my all-time favorite quotes:

Unless you’re completely exploded, there’s always something to be grateful for.

After hearing the Counting Crows song, I considered taking a stab at reading or rereading all of his work—which to the best of my knowledge includes 14 novels and novellas, four short story collections, and one play.

I don’t know if I’ll achieve that objective, but I found some writing about him in various publications that definitely amped up my interest. I recently obtained a copy of Collected Stories, published in 2001, and plan to reread The Adventures of Augie March after I finish it.

Will this be the thread that pulls in the words, images, emotions, and ideas I think I’m missing? I don’t know. Salmon Rushdie said, “[Bellow’s] body of work is more capacious of imagination and language than anyone else’s.”

Capacious of imagination. I love that! It seems like a great place to begin.